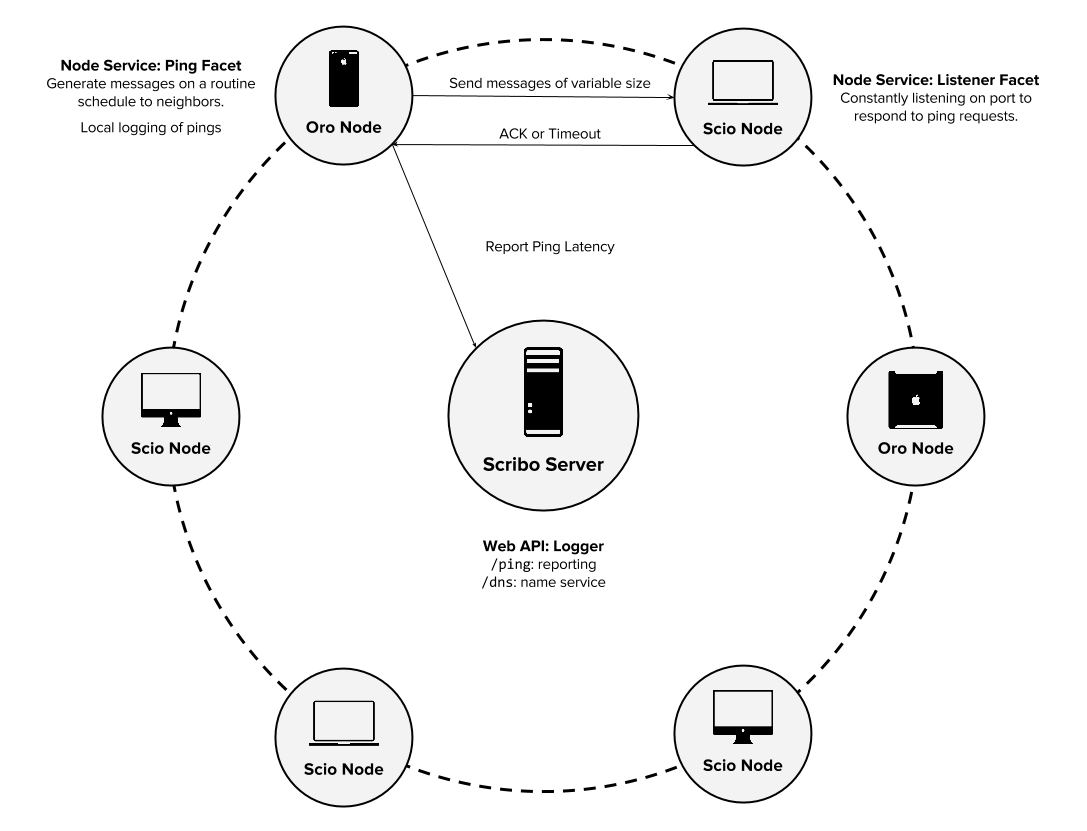

Yesterday I built my first microservice (a RESTful API) using Go, and I wanted to collect a few of my thoughts on the experience here before I forgot them. The project, Scribo, is intended to aid in my research by collecting data about a specific network that I’m looking to build distributed systems for. I do have something running, which will need to evolve a lot, and it could be helpful to know where it started.

When I first sat down to do this project, I thought it was pretty straight forward. I watched “Writing JSON REST APIs in Go (Go from A to Z)” and read through the “Making a RESTful JSON API in Go” tutorial. I was going to deploy the service on Heroku, add testing with Ginkgo and Gomega, and use continuous integration with Travis-CI. I was used to doing the same kind of thing with Flask or Django and figured it couldn’t take that long. After a full day of coding, I did manage to do all the things I mentioned above, but with a number of angsty decisions that have caused me to write this post.

There were three main holdups that caused me to have trouble moving forward quickly:

- The choice of a RESTful API framework

- Structuring the project

- Managing dependencies and versions

Briefly I want to go over how each went down and the choices I made.

Framework

At the moment I’ve ended up using Gorilla mux though it was in pretty strong contention with go-json-rest. Note that these frameworks were the two proposed in both of the tutorials I mentioned earlier. I saw but did not consider Martini, which is no longer maintained, and Gin which apparently is Martini-like but faster. I was warned off of these frameworks by a post by Stephen Searles even though the majority of tutorials on the first page of Google results mentioned and used these frameworks.

I think the response by Code Gangsta to Searles’ criticism highlights the trouble that I had selecting a framework. I was expecting to come in and have to perform some hoop jumping to select a framework sort of like Flask vs. Django or Sinatra vs. Rails. I hoped that I would have been easily steered away from projects like Bottle (not a bad project, just not very popular) simply because of the number of tutorials.

The issue is that Go is so new and Go developers come from other communities, that idiomatic Go frameworks are still pretty tough to write because a lot of thought has to go into what that means. Moreover, Go’s standard library, namely net/http is so good that you don’t really have to build a lot on top of it (whereas you would never build a web app directly on top of Python’s HTTPServer).

Go is intended to be the compilation of small, lightweight packages that are very good at the one thing they do well. It is not intended for large frameworks. Even Gorilla seems a bit to large with this context. I guess what I want is some small lightweight Resource API like the one described in “A RESTful Microframework in Go” — which I intend to build for my platform. Since we can’t be expected to build all these small components on our own this me led to the next problem: packaging.

Project Structure

There is actually a lot about how to structure Go code, in fact it is one of the first things discussed in the Go documentation. This is because the Go tools are dependent on how you organize your projects. The src/pkg/bin structuring along with namespaces based on repositories and use of go get to fetch and manage dependencies (see next section) makes Go “open source ready”.

However, at the end of the day, it still feels weird for me to create multiple repositories for a single project – particularly as it seems that they are suggesting that you create your library in one repository, and your commands and program main.go in a second repository. Moreover, I don’t like my code to be at the top level of the repository, I need some organization for large projects that don’t span repositories, and would like things to be in a subfolder (maybe I’ll get over this and be a better Go programmer).

Based on Heroku’s suggestions, I followed the advice of Ben Johnson in “Structuring Applications in Go”. I put my main.go in a cmd folder so that it wouldn’t be built automatically on go get. My library I still forced into a subpackage, which requires me to specify ./... for most go commands to recursively search the directory for Go code. I’m decently ok with how things are now, but still not wholley comfortable.

Also - this is a web application, so I need to add HTML, CSS, and JavaScript files. Where to put those? Right now they’re in the root of the directory, but honestly this doesn’t feel right. I just wanted to create a small and simple one page app to view the microservice under the hood. The essential problem was that I couldn’t find a single example of a web app built using Go. This is a matter of not being able to Google correctly for it, but I still need those examples!

Dependency Management

Apparently there was some discussion in Go between when I first started using it (1.3) and when I came back to it (1.6), and during Go 1.5 there was a “vendor experiment”. Vendoring is a mechanism of preserving specific dependency requirements for a project by including them (usually in a subfolder called vendor) in the source version control for your project. This is opposed to other mechanisms where you simply specify the version of the dependency you want and can fetch it (e.g. with go get) during the build process.

From what I can tell, the vendor experiment one, and dependency management tools like Godep and The Vendor tool for Go had to do a bit of reorganizing. Because of Travis-CI and Heroku (which automatically look for a folder in your project called Godeps, created by the godep save command), I went with Godep over anything else.

Still I’m not happy with this solution. I have no guide about what projects to select or use. Moreover, my src/github.com directory is getting filled up with a TON of projects. I feel like more investigation needs to be done here as well.

Conclusion

Yesterday I was super excited, today I’m nervous but ready. I have a lot of questions, but I hope that I’ll be moving forward to doing some serious Go programming in the future. I hope to be as good a Go programmer as I am a Python programmer in the future, so that I can naturally create fast, effective systems.