For close-to-open consistency, we need to be able to implement a file system that can detect atomic changes to a single file. Most programming languages implement open() and close() methods for files - but what they are really modifying is the access of a handle to an open file that the operating system provides. Writes are buffered in an asynchronous fashion so that the operating system and user program don’t have to wait for the spinning disk to figure itself out before carrying on. Additional file calls such as sync() and flush() give the user the ability to hint to the OS about what should happen relative to the state of data and the disk, but the OS provides no guarantees that will happen.

We use the FUSE library provided by bazil.org/fuse to implement a file system in user space. FUSE receives kernel calls to file system methods and passes them to a server - developers can write handlers for requests and return responses. Unfortunately, while there is an Open() method that returns the handle to an open file, there is no equivalent Close() method. Instead FUSE allows external processes to make calls to Read(), Write(), Flush(), and Fsync(). This led us to the obvious question - when reading and writing files, what calls are being made to the file system?

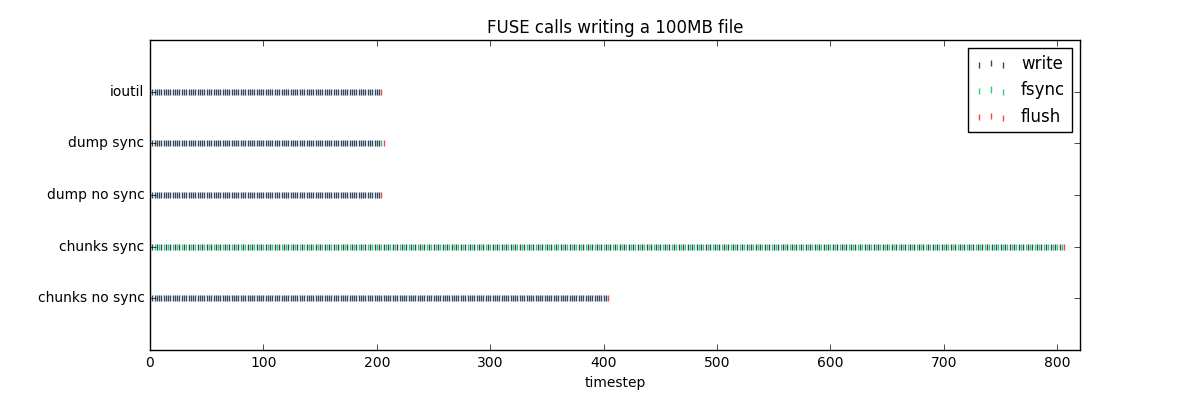

To answer this question, we wrote a Go program that wrote random data to a file. There are many ways to write to a file, as explained by Go by Example. So we implemented several methods (discussed below). We then ran the data writer program into a file on an in-memory FUSE server that logged different calls. The results are shown below:

The bottom line is that Fsync() is on called when the user program calls it - essential for Vim and Emacs, but a hint only. Flush() is always called at close, and Write() is called many times from open to close. The names on the Y-axis describe the various methods of writing to a file I will discuss next.

The first step is to generate random data with n bytes. To do this, I chose to write random alphabetic characters to the file, along with a couple of white space characters. The Go function used to implement this is as follows:

var letterRunes = []rune("abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz\n ")

func randString(n int) string {

b := make([]rune, n) // Make a rune slice of length n

// For every position in b, assign a random rune

for i := range b {

b[i] = letterRunes[rand.Intn(len(letterRunes))]

}

// Convert the rune to a string and return

return string(b)

}

The easiest method to write data to a file is to use the ioutil package - just supply a path, data, and a file mode and ioutil will do all the rest. This is the common mechanism I use for reading and writing files, so we were very interested to see how Go handled files from the file system perspective. Implementing this function is easy:

data := []byte(randString(1.049e+8))

err := ioutil.WriteFile("test.txt", data, 0644)

All we have to do is create a 100MB slice of random data and send it to test.txt - easy! Under the hood, it appears that Go is writing blocks of 1,048,576 (1MB) to the file at a time, then calling access, attrs, and flushing the data. A snippet of the log output shows the sequence of actions:

...

wrote 1048576 bytes offset by 100663296 to file 2

wrote 1048576 bytes offset by 101711872 to file 2

wrote 1048576 bytes offset by 102760448 to file 2

wrote 1048576 bytes offset by 103809024 to file 2

wrote 42400 bytes offset by 104857600 to file 2

access called on node 2

getting attrs on node 2

flush file 2 (dirty: true, contains 104900000)

getting attrs on node 2

...

The ioutil package appears to be just a wrapper function around the standard mechanism of opening the file, writing, syncing, and closing the file. We call this the “dump” method since we’re just sticking the data all into disk at once. However, even though we call Write() with the complete data slice, only 1MB is passed to the FUSE Write handler at a time.

fobj, err := os.Create("test.txt")

check(err)

defer fobj.Close()

_, err = fobj.Write([]byte(randString(1.049e+8)))

check(err)

fobj.Sync()

Note the last call to fobj.Sync(), if we omit this call (dump no sync) then FUSE never sees an fsync event and all is well. No matter what, though, Flush is called (probably by fobj.Close()). Since Go is clearly doing some chunking and writing, my last thought was to try to do my own chunking, below Go’s 1MB chunks and see if any arbitrary fsync calls occurred as Go was managing the handle to the open file.

fobj, err := os.Create(path)

check(err)

defer fobj.Close()

nbytes := 1.049e+8

chunks := 524288

for i := 0; i < nbytes; i += chunks {

var n int

if nbytes-i < chunks {

n = nbytes - i

} else {

n = chunks

}

_, err = fobj.Write([]byte(randString(n)))

check(err)

err = fobj.Sync()

check(err)

}

However, as shown in the graph, fsync was only called if it was directly called by the user code. Note that on our file system, it took between 6 and 10 seconds to write the 100MB file to disk. There was plenty of occasion for Go’s routine functionality (garbage collection, etc.) to run during the processing of the file.

For more information to experiment with different calls, check out the complete write.go command on Gist.