The Filesystem in Userspace (FUSE) software interface allows developers to create file systems without editing kernel code. This is especially useful when creating replicated file systems, file protocols, backup systems, or other computer systems that require intervention for FS operations but not an entire operating system. FUSE works by running the FS code as a user process while FUSE provides a bridge through a request/response protocol to the kernel.

In Go, the FUSE library is implemented by bazil.org/fuse. It is a from-scratch implementation of the kernel-userspace communication protocol and does not use the C library. The library has been excellent for research implementations, particularly because Go is such an excellent language (named programming language of 2016). However, it does lead to some questions (particularly because of the questions in the Go documentation):

- How is the performance of bazil.org/fuse?

- How complete is the implementation of bazil.org/fuse?

- How does bazil.org/fuse compare to a native system?

In order to start taking a look at these questions, I created an in-memory file system using bazil.org/fuse called MemFS. The bazil.org/fuse library works by providing many interfaces to define a File System (fs.FS* interfaces), Nodes (fs.Node* interfaces) that represent files, links, and directories, and Handles (fs.Handle* interfaces) to open files. A file system that uses bazil.org/fuse must create Go objects that implement these interfaces then pass them to the FUSE server which makes calls to the relevant methods. The goal of MemFS was to provide as complete an implementation of every single interface as possible (since I have yet to find a reference implementation that does do this).

In order to evaluate the performance of MemFS vs. the normal file system on my MacBook pro, I created the following protocol, implemented by a simple Python script:

- Clone a repository into the file system

- Make/build the software in the repository

- Traverse the file system and stat every file

- Collect time and FS meta data information

I then compared MemFS performance to normal FS performance for several popular large and small C applications including databases, web servers, and programming languages:

- Redis (76MB, 591 files, 137,475 LOC)

- Postgres (422MB, 4,807 files, 910,948 LOC)

- Nginx (62MB, 440 files, 155,056 LOC)

- Apache Web Server (362MB, 4,059 files, 503,006 LOC)

- Ruby (197MB, 3,281 files, 918,052 LOC)

- Python 3 (382MB, 3,570 files, 931,814 LOC)

Unfortunately due to vagaries in the build process with Postgres, Apache Httpd, Ruby, and Python I can only report on Redis and Nginx. But more on that later.

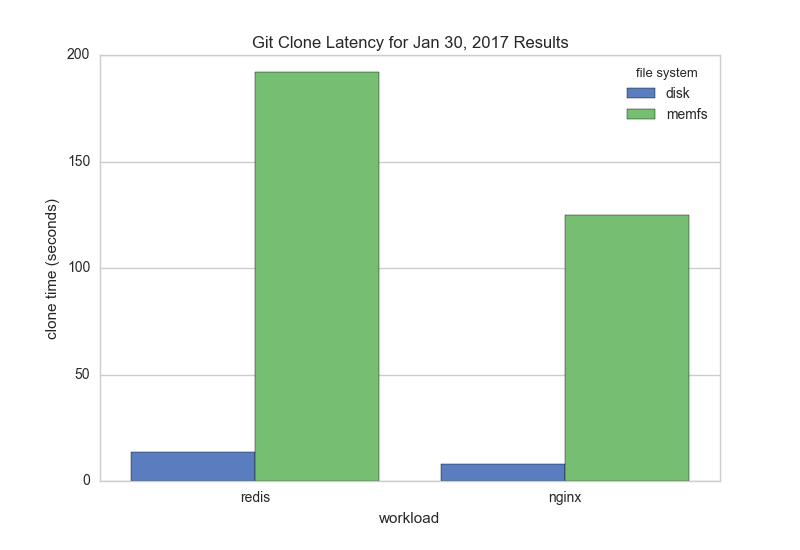

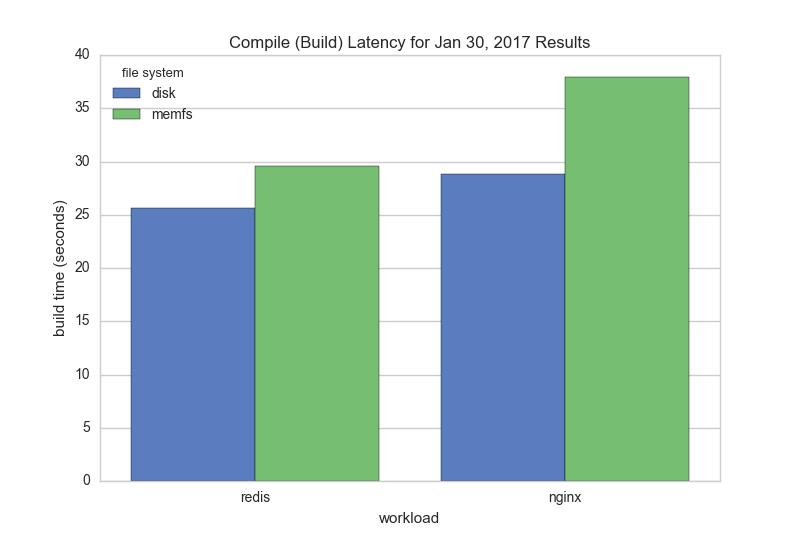

The workload code can be found at github.com/bbengfort/compile-workload along with a benchmark.sh script that executes the full test-suite. Here are the time results for the OS X file system (OS X) vs. MemFS for both cloning and compiling:

As you can see from the graphs, git clone is horribly slow on MemFS. Further investigation revealed that git is writing 4107 bytes of data at a time as it downloads its compressed pack file. This means approximately 255 times more calls to the Write() FUSE method than other file writing mechanisms which typically write 1MB at a time. Because each call to Write() must be handled by the FUSE server and responded to by MemFS (which is allocating an byte slice under the hood), the more calls to Write() the exponentially worse the system is.

Compiling, on the other hand, is supposed to be more representative of a workload - containing many reads, writes, and stats in a controlled sequence of events. For both Redis and Nginx, MemFS does add some overhead to compilation, but not nearly as much as git clone did. Note that downloading a zip file from GitHub and then building it exhibited a similar shape to the compiling graph.

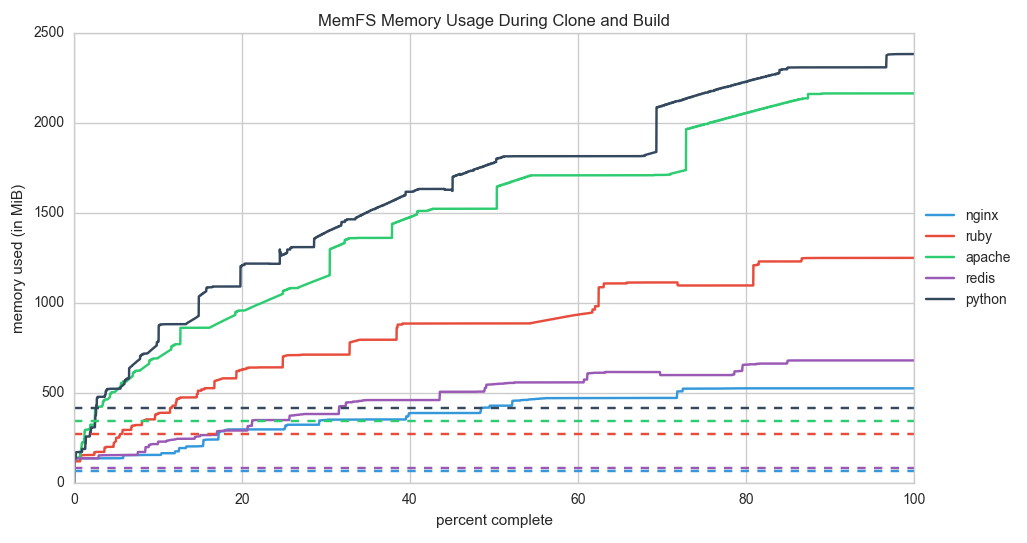

Memory usage for MemFS is currently atrocious, however:

The dotted lines are the maximum file usage on disk according to a recursive stat of each file. The solid lines are the memory usage of MemFS during clone and build. Although some extra memory overhead is expected to maintain the journal and references to the file system tree, the amount of overhead necessary seems completely out of whack compared to the storage requirements. Some investigation about freeing data is necessary.

Finally the last, critical lesson. The reason only Redis and Nginx are represented in the graph is because the other builds failed for one reason or another. The cause of the build failures is primarily due to my goal to implement 100% of the FUSE interface methods. However this is not how bazil.org/fuse works and in fact 100% interface implementation is exactly the wrong thing to do.

Take for example the ReadAll() vs. Read() methods that implement HandleReadAller and HandleReader respectively. I attempted to implement both and kept receiving different build errors, though I did notice the clone and compile behavior changing as I messed with these two methods. It turns out that the bazil.org/fuse server implementation checks to see if the FS implements HandleReadAller and if so, returns the result from ReadAll, otherwise it enforces HandleRead and sends the Read method the request and response from FUSE.

My hypothesis as to why cloning was failing when I had implemented ReadAll is simple. The Read method allows the client to specify an offset in the file to read from and a size of data to respond with. Presumably git clone was attempting to read the last 32 bytes of the compressed pack file (or something like that) so it could perform a CRC check or some other data validation. FUSE, however, returned all of the data rather than just the data from the offset because ReadAll was implemented. As a result, git clone choked with a stream error.

The bottom line is that FUSE allows some interfaces for convenience only for higher level FS implementations. MemFS, however, needs to support only the low level FUSE serve interactions. As a general rule of thumb, if the interface method takes a request and response object and simply returns an error - then that FUSE method is probably at a bit lower of a level, exactly what MemFS is looking for.