I have had some recent discussions regarding cacheing to improve application performance that I wanted to share. Most of the time those conversations go something like this: “have you heard of Redis?” I’m fascinated by the fact that an independent, distributed key-value store has won the market to this degree. However, as I’ve pointed out in these conversations, cacheing is a hierarchy (heck, even the processor has varying levels of cacheing). Especially when considering micro-service architectures that require extremely low latency responses, cacheing should be a critical part of the design, not just a bolt-on after thought!

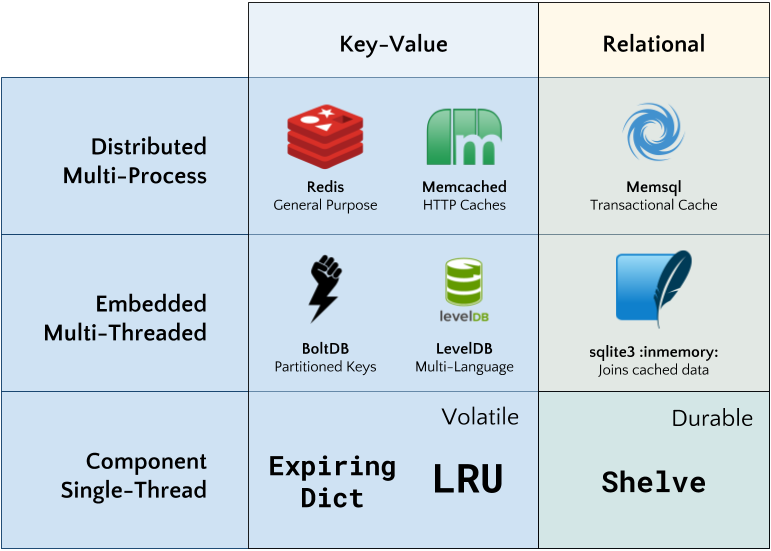

So here are the tools I consider when implementing cacheing, in a hierarchy from single process to distributed processes:

In a later post, I may review embedded, multi-threaded, or external multi-process cacheing. In this post, however, I’m focused on component based single thread cacheing. But before we discuss that let’s review why cacheing is important. A definition:

Cacheing: storing a computed value in a quickly readable data structure (usually in memory) to reduce the amount of time to respond to API calls usually by minimizing the need for repeated computation.

The idea is that computing a value takes a measurable amount of time, either from processor cycles or I/O from the disk or another data source. By storing the computed value, repeated calls with a similar input can benefit from fast lookups in memory. Let’s look at a simple example of this, a process called memoization:

from functool import wraps

def memoized(fget):

attr_name = '_{0}'.format(fget.__name__)

@wraps(fget)

def fget_memoized(self):

if not hasattr(self, attr_name):

setattr(self, attr_name, fget(self))

return getattr(self, attr_name)

return property(fget_memoized)

This snippet of code is so common that it is seen in a utils module in almost every larger piece of software I write. The memoized function is a method decorator (for classes) that acts similarly to the @property decorator. When a class attribute is accessed, its value corresponds to the return value of the fget function. When used with fget_memoized, however, the fget function is called, stored on the object, and instead of calling fget repeatedly, the cached value is returned. For example:

class Thing(object):

@memoized

def prime(self):

print("long running computation!")

return 31

The print statement will only occur once, on the first access to thing.prime. After that, all calls will return the value of thing._prime. To force a recomputation you can simply del thing._prime.

This is great, and extremely commonly used — but what if you want to cache the response by input or timeout the cache after a fixed period? The answer to the first is the lru_cache, which caches values, discarding the “least recently used” first. Therefore if you have a function that accepts an argument:

from functools import lru_cache

@lru_cache(maxsize=256)

def fib(n):

if n < 2:

return n

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

Then the cache will store values for that argument until maxsize is reached, at which point values used least recently will be discarded. Note that it is best to use a maxsize value that is a power of 2 for best performance. You can also inspect the cache as follows:

>>> fib(31)

1346269

>>> fib.cache_info()

CacheInfo(hits=29, misses=32, maxsize=256, currsize=32)

To expire a value after a specific amount of time, I recommend using an ExpiringDict as follows:

from expiringdict import ExpiringDict

cache = ExpiringDict(max_len=256, max_age_seconds=2)

You can now get and put values into the cache:

import time

cache["foo"] = "bar"

cache.get("foo") # bar

time.sleep(2)

cache.get("foo") # None

On get, the ExpiringDict checks the number of seconds since the value was inserted into the dictionary. If it is longer than the max_age the value is deleted and None is returned. Note that the cache is only managed on access, therefore without a max_length, they can grow to infinite size if not cleaned up. One way to manage this is with a routine garbage collection thread that just performs a get on all values, locking the dictionary as it does.

Neither of these types of caches are persistent. In order to persist a cache to disk, you can simply pickle the object to disk. However, a better option might be the Python shelve module.

A “shelf” is a persistent, dictionary-like object that stores Python objects to disk. By itself, it is not a cache per-se, but with the writeback flag set to True, it can be used as a durable cache. In this case, entries are cached and accessed in memory, and only snapshotted to disk on sync and close.

from shelve import shelve

class DurableCache(object):

def __init__(self, path):

self.db = shelve.open(path, writeback=True)

def put(self, key, val):

self.db[key] = val

def get(self, key):

return self.db[key]

def close(self):

self.db.close()

def sync(self):

self.db.sync()

With a little creativity, these caches can be extremely effective local durable storage. However note that the shelf does not know when an object has been mutated, which means it can consume a lot of memory or take a long time to sync or close. Advanced in-memory caches that use the shelve module add logic to detect these things and background routines to clean up and periodically checkpoint to disk for recovery.

There is still a long way to go with cacheing options, including embedded and in-memory databases as well as external caches for multi-process or distributed cacheing. I may discuss these in another post.