This is just a quick note on the performance of writing to a file on disk using Go, and reveals a question about a common programming paradigm that I am now suspicious of. I discovered that when I wrapped the open file object with a bufio.Writer that the performance of my writes to disk significantly increased. Ok, so this isn’t about simple file writing to disk, this is about a complex writer that does some seeking in the file writing to different positions and maintains the overall state of what’s on disk in memory, however the question remains:

Why do we buffer our writes to a file?

A couple of answers come to mind: safety, the buffer ensures that writes to the underlying writer are not flushed when an error occurs; helpers, there may be some methods in the buffer struct not available to a native writer; concurrency, the buffer can be appended to concurrently with another part of the buffer being flushed.

However, we determined that in performance critical applications (file systems, databases) the buffer abstraction adds an unacceptable performance overhead. Here are the results.

Results

First, we’re not doing a simple write - we’re appending to a write-ahead log that has fixed length metadata at the top of the file. This means that a single operation to append data to the log consists of the following steps:

- Marshal data to bytes

- Write data to end of the log file (possibly sync the file)

- Seek to the top of the file

- Marshall and write fixed length meta data header

- Seek to the bottom of the file

- Sync the file to disk

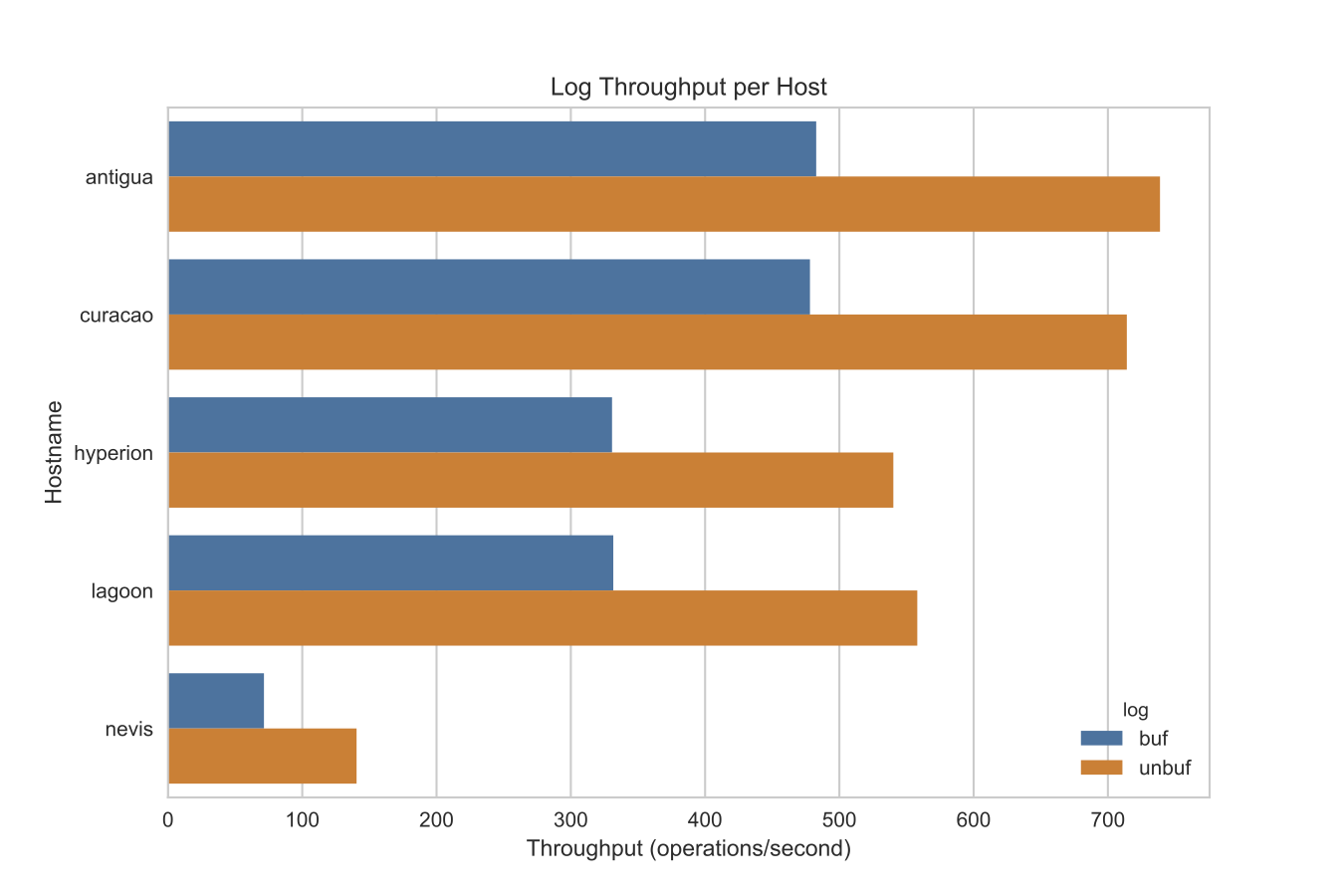

So there is a bit more work here than simply throwing data at disk. We can see in the following graph that the performance of the machine (CPU, Memory, and Disk) plays a huge role in determining the performance of these operations in terms of the number of these writes the machine is able to do per second:

In the above graph, Hyperion and Lagoon are Dell Optiplex servers and Antigua, Curacao, and Nevis are Intel NUCs. They all have different processors and SSDs, but all have 16GB memory. For throughput, bigger is better (you can do more operations per second). As you can see on all of the servers, there is about a 1.6x increase in throughput using unbuffered writes to the file over buffered writes to the file.

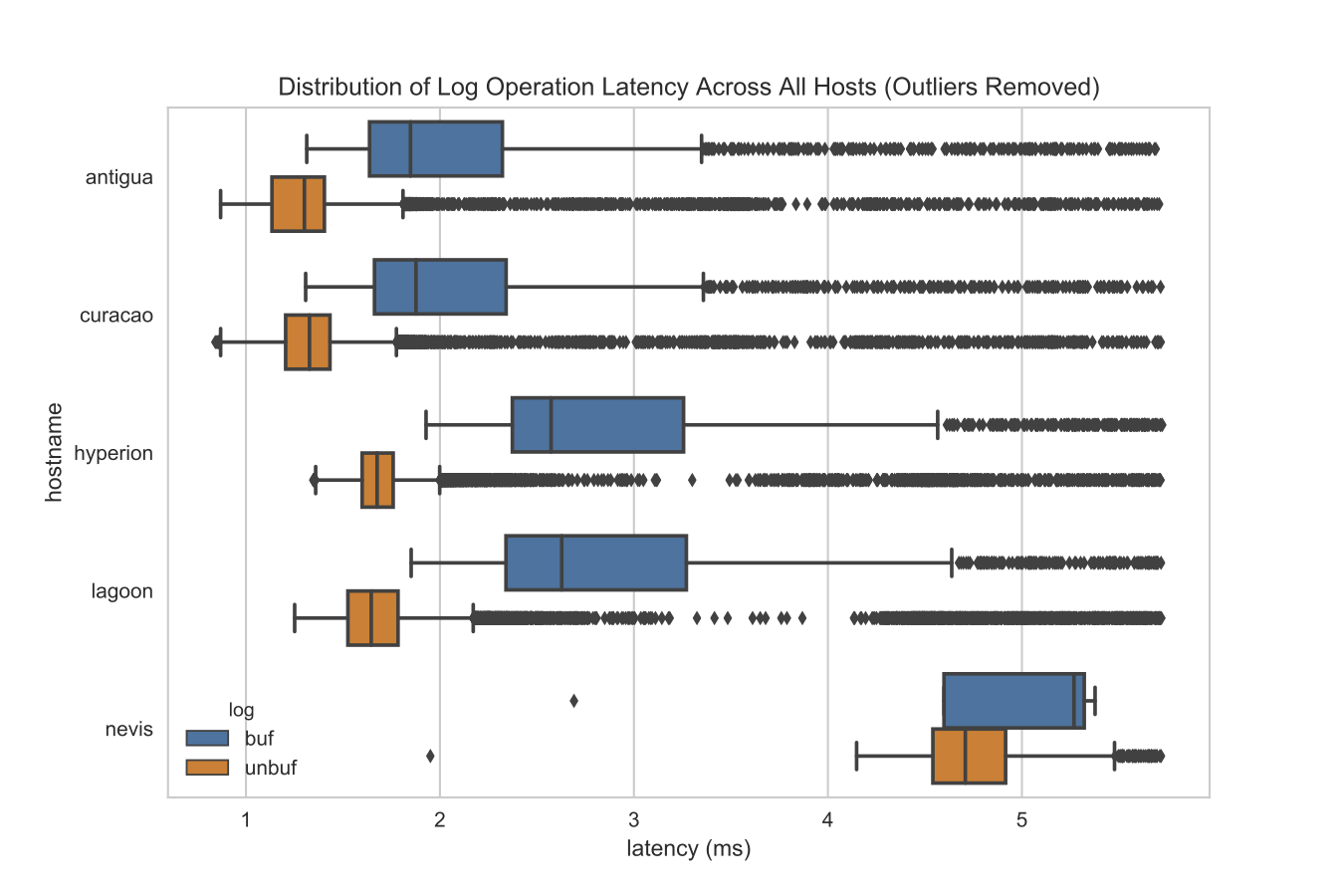

We can inspect the distribution of the latency of each individual operation as follows (with latency, smaller is better — you’re doing operations faster):

The boxplot shows the distribution of latency such that the box is between the 25th and 75th percentile (with a bisecting line at the median) - the lines are from the 5th to the 95th percentile, and anything outside the lines are considered outliers and are visualized as diamonds.

We can see the shift not just in the mean, but also the median; a 1.6 increase in speed (decrease in latency) from buffered to unbuffered writes. More importantly, we can see that unbuffered writes are more consistent; e.g. they have a tighter distribution and less variable operational latency. I suspect this means that while both types of writes are bound by disk accesses from other processes, buffered writes are also bound by CPU whereas unbuffered writes are less so.

Method

The idea here is that we are going to open a file and append data to it, tracking what we’re doing with a fixed length metadata header at the beginning of the file. Creating a struct to wrap the file and open, sync, and close it is pretty straight forward:

type Log struct {

path string

file *os.File

}

func (l *Log) Open(path string) (err error) {

l.path = path

l.file, err = os.OpenFile(path, os.O_WRONLY|os.O_CREATE, 0644)

if err != nil {

return err

}

}

func (l *Log) Close() error {

err := l.file.Close()

l.file = nil

return err

}

func (l *Log) Sync() error {

return l.file.Sync()

}

Now let’s say that we have an entry that knows how to write itself to an io.Writer interface as follows:

type Entry struct {

Version uint64 `json:"version"`

Key string `json:"key"`

Value []byte `json:"value"`

Created time.Time `json:"created"`

}

func (e *Entry) Dump(w io.Writer) (int64, error) {

// Encode entry as JSON data (base64 enocded bytes value)

data, err := json.Marshal(e)

if err != nil {

return -1, err

}

// Add a newline to the data for json lines format

data = append(data, byte('\n'))

// Write the data to the writer and return.

return w.Write(data)

}

So the question is, if we have a list of entries we want to append to the log, how do we pass the io.Writer to the Entry.Dump method in order to write them one at a time?

The first method is the standard method, buffered, using bufio.Writer:

func (l *Log) Append(entries ...*Entry) (size int64, err error) {

// Crate the buffer and define the bytes

bytes := 0

buffer := bufio.NewWriter(l.file)

// Write each entry keeping track of the amount of data written

for _, entry := range entries {

if bytes, err = entry.Write(buffer); err != nil {

return -1, err

} else {

size += bytes

}

}

// Flush the buffer

if err = buffer.Flush(); err != nil {

return -1, err

}

// Sync the underlying file

if err = l.Sync(); err != nil {

return -1, err

}

return size, nil

}

As you can see, even though we’re getting a buffered write to disk, we’re not actually leveraging any of the benefits of the buffered write. By eliminating the middleman with an unbuffered approach:

func (l *Log) Append(entries ...*Entry) (size int64, err error) {

// Write each entry keeping track of the amount of data written

for _, entry := range entries {

if bytes, err := entry.Write(buffer); err != nil {

return -1, err

} else {

size += bytes

}

}

// Sync the underlying file

if err = l.Sync(); err != nil {

return -1, err

}

return size, nil

}

We get the performance benefit as shown above. Now, I’m not sure if this is obvious or not; but I do know that it’s commonly taught to wrap the file object with the buffer; the unbuffered approach may be simpler and faster but it may also be less safe, it depends on your use case.