Building correct concurrent programs in a distributed system with multiple threads and processes can quickly become very complex to reason about. For performance, we want each thread in a single process to operate as independently as possible; however anytime the shared state of the system is modified synchronization is required. Primitives like mutexes can [ensure structs are thread-safe]({% post_url 2017-02-21-synchronizing-structs %}), however in Go, the strong preference for synchronization is communication. In either case Go programs can quickly become locks upon locks or morasses of channels, incurring performance penalties at each synchronization point.

The Actor Model is a solution for reasoning about concurrency in distributed systems that helps eliminate unnecessary synchronization. In the actor model, we consider our system to be composed of actors, computational primitives that have a private state, can send and receive messages, and perform computations based on those messages. The key is that a system is composed of many actors and actors do not share memory, they have to communicate with messaging. Although Go does not provide first class actor primitives like languages such as Akka or Erlang, this does fit in well with the CSP principle.

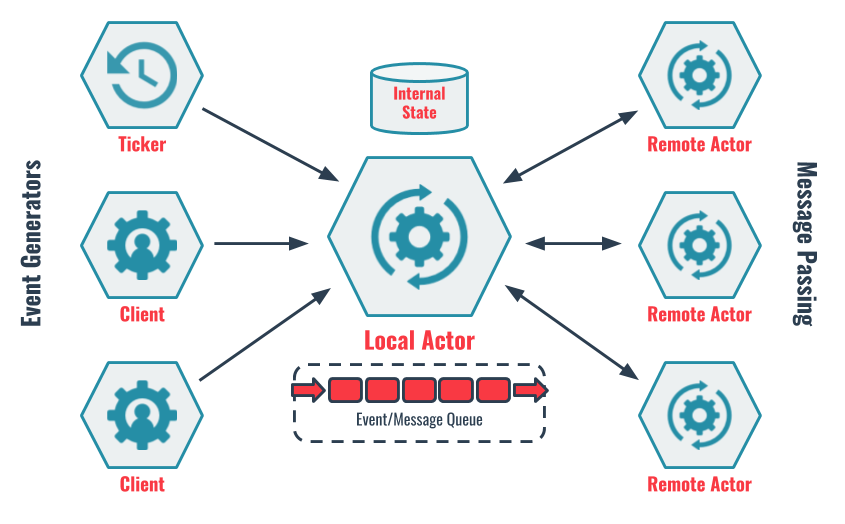

In the next few posts, I’ll explore implementing the Actor model in Go for a simple distributed system that allows clients to make requests and periodically synchronizes its state to its peers. The model is shown below:

Actors

An actor is a process or a thread that has the ability to send and receive messages. When an actor receives a message it can do one of three things:

- Create new actors

- Send messages to known actors

- Can designate how you handle the next message

At first glance we may think that actors are only created at the beginning of a program, e.g. the “main” actor or the instantiation of a program-long ticker actor that sends periodic messages and can receive start and stop messages. However, anytime a go programmer executes a new go routine, there is the possibility of a new actor being created. In our example, we’ll explore how a server creates temporary actors to handle single requests from clients.

Sending messages to known actors allows an actor to synchronize or share state with other go routines in the same process, other processes on the same machine, or even processes on other machines. As a result, actors are a natural framework for creating distributed systems. In our example we’ll send messages both with channels as well as using gRPC for network communications.

The most important thing to understand about actor communication is that although actors run concurrently, they will only process messages sequentially in the order which they are received. Actors send messages asynchronously (e.g. an actor isn’t blocked while waiting for another actor to receive the message). This means that messages need to be stored while the actor is processing other messages; this storage is usually called a “mailbox”. We’ll implement mailboxes with buffered channels in this post.

Deciding how to handle the next message is a general way for saying that actors “do something” with messages, usually by modifying their state, and that it is something “interesting enough” that it impacts how the next message is handled. This implies a couple of things:

- Actors have an internal state and memory

- Actors mutate their state based on messages

- How an actor responds depends on the order of messages received

- Actors can shutdown or stop

For the rest of the posts, we’ll consider a simple service that hands out monotonically increasing, unique identities to clients called Ipseity. If the actor receives a next() message, it increments it’s local counter (mutating it’s internal state) ensuring that the next message always returns a monotonically increasing number. If it receives an update(id) message, it updates it’s internal state to specified id if it is larger than its internal id, allowing it to synchronize with remote peers (in an eventually consistent fashion).

Event Model

In order to reduce confusion between network messages and actor messages, I prefer to use the term “event” when referring to messages sent between actors. This also allows us to reason about actors as implementing an event loop, another common distributed systems design paradigm. It is important to note that “actors are a specialized, opinionated implementation of an event driven architecture”, which means the actor model is a subset of event architectures, such as the [dispatcher model]({% post_url 2017-07-21-event-dispatcher %}) described earlier in this journal.

I realize this does cause a bit of cognitive overhead, but this pays off when complex systems with many event types can be traced, showing a serial order of events handled by an actor. So for now, we’ll consider an event a message that can be “dispatched” (sent) to other actors, and “handled” (received) by an actor, one at a time.

Events are described by their type, which determines what data the event contains and how it should be handled by the actor. In Go, event types can be implemented as an enumeration by extending the uint16 type as follows:

// Event types represented in Ipseity

const (

UnknownEvent EventType = iota

IdentityRequest

SyncTimeout

SyncRequest

SyncReply

)

// String names of event types

var eventTypeStrings = [...]string{

"unknown", "identityRequest", "syncTimeout", "syncRequest", "syncReply",

}

// EventType is an enumeration of the kind of events that actors handle

type EventType uint16

// String returns the human readable name of the event type

func (t EventType) String() string {

if int(t) < len(eventTypeStrings) {

return eventTypeStrings[t]

}

return eventTypeStrings[0]

}

Events themselves are usually represented by an interface to allow for multiple event types with specialized functionality to be created in code. For simplicity here, however, I’ll simply define a single event struct and we’ll use type casting later in the code:

type Event struct {

Type EventType

Source interface{}

Value interface{}

}

The Source of the event is the actor that is dispatching the event, and we’ll primarily use this to store channels so that we can send messages (events) back to the actor. The Value of the event is any associated data that needs to be used by the actor processing the event.

Actor Interface

There are a lot of different types of actors including:

- Actors that run for the duration of the program

- Actors that generate events but do not receive them

- Actors that exist ephemerally to handle one or few events

As a result it is difficult to describe an interface that handles all of these types generically. Instead we’ll focus on the central actor of our application (called the “Local Actor” in the diagram above), which fulfills the first role (runs the duration of the program) and most completely describes the actor design.

type Actor interface {

Listen(addr string) error // Run the actor to listen for messages

Dispatch(Event) error // Outside callers dispatch events to actor

Handle(Event) error // Handle each event sequentially

}

As noted in the introduction and throughput appendix below, there are a number of ways to implement the actor interface that ensure events received by the Dispatch method are handled one at a time, in sequential order. Here, we’ll use a a buffered channel as a mailbox of a fixed size, so that other actors that are dispatching events to this actor aren’t blocked while the actor is handling other messages.

type ActorServer struct {

pid int64 // unique identity of the actor

events chan Event // mailbox to receive event dispatches

sequence int64 // internal state, monotonically increasing identity

}

The Listen method starts the actor, (as well as a gRPC server on the specified addr, which we’ll discuss later) and reads messages off the channel one at a time, executing the Handle method for each message before moving to the next message. Listen runs forever until the events channel is closed, e.g. when the program exits.

func (a *ActorServer) Listen(addr string) error {

// Initialize the events channel able to buffer 1024 messages

a.events = make(chan Event, 1024)

// Read events off of the channel sequentially

for event := range a.events {

if err := a.Handle(event); err != nil {

return err

}

}

return nil

}

The Handle method can create new actors, send messages, and determine how to respond to the next event. Generally it is just a jump table, passing the event to the correct event handling method:

func (a *ActorServer) Handle(e Event) error {

switch e.Type() {

case IdentityRequest:

return a.onIdentityRequest(e)

case SyncTimeout:

return a.onSyncTimeout(e)

case SyncRequest:

return a.onSyncRequest(e)

case SyncReply:

return a.onSyncReply(e)

default:

return fmt.Errorf("no handler identified for event %s", e.Type())

}

}

The Dispatch method allows other actors to send events to the actor, by simply putting the event on the channel. When other go routines call Dispatch they won’t be blocked, waiting for the actor to handle the event because of the buffer … unless the actor has been backed up so the buffer is full.

func (a *ActorServer) Dispatch(e Event) error {

a.events <- e

return nil

}

Next Steps

In the next post (or two) we’ll hook up a gRPC server to the actor so that it can serve identity requests to clients as well as send and respond to synchronization requests for remote actors. We’ll also create a second go routine next to the actor process that issues synchronization timeouts on a periodic interval. Together, the complete system will be able to issue monotonically increasing identities in an eventually consistent fashion.

Other Resources

For any discussion of Actors, it seems obligatory to include this very entertaining video of Carl Hewitt, the inventor of the actor model, describing them on a white board with Erik Meijer and Clemens Szyperski.

Other blog posts:

- The actor model in 10 minutes

- Why has the actor model not succeeded?

- Understanding reactive architecture through the actor model

Appendix: Throughput

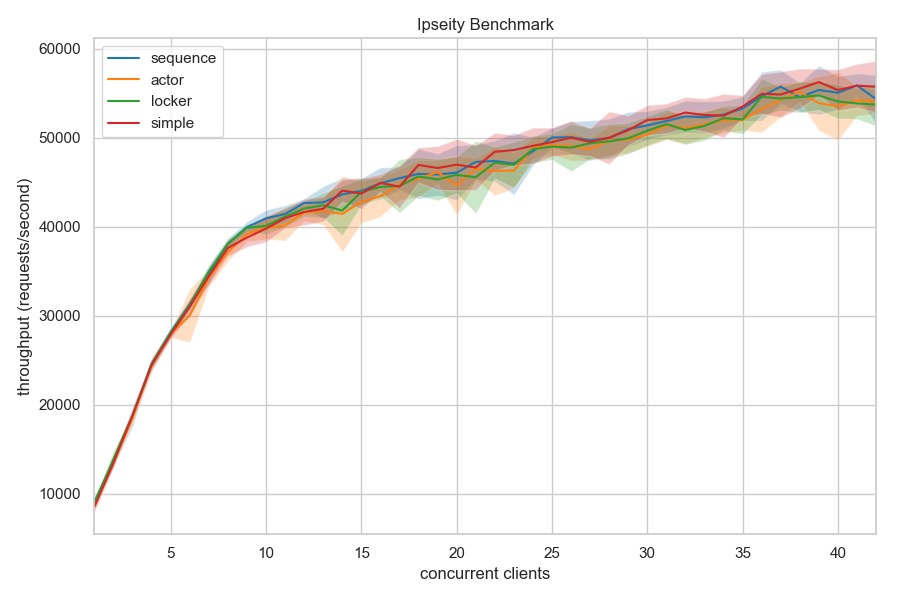

One of the biggest questions I had was whether or not the actor model introduced any performance issues over a regular mutex by serializing a wrapper event over a channel instead of directly locking the actor state. I tested the throughput for the following types of ipseity servers:

- Simple: locks the whole server to increment the

sequenceand create the response to the client. - Sequence: creates a sequence struct that is locked when incremented, but not when creating the response to the client.

- Actor: Uses the buffered channel actor model as described in this post.

- Locker: Implements the actor interface but instead of a buffered channel uses a mutex to serialize events.

As you can see from the above benchmark, it does not appear that the actor model described in these posts adds overhead that penalizes performance.

The code for both the benchmark and the implementations of the servers above can be found at: https://github.com/bbengfort/ipseity/tree/multiactor