In order to improve the performance of asynchronous message passing in Alia, I’m using gRPC bidirectional streaming to create the peer to peer connections. When the replica is initialized it creates a remote connection to each of its peers that lives in its own go routine; any other thread can send messages by passing them to that go routine through a channel, replies are then dispatched via another channel, directed to the thread via an actor dispatching model.

This post is about the performance of the remote sending go routine, particularly with respect to how many threads that routine is. Here is some basic stub code for the messenger go routine that listens for incoming messages on a buffered channel, and sends them to the remote via the stream:

func (r *Remote) messenger() {

// Attempt to establish a connection to the remote peer

var err error

if err = r.connect(); err != nil {

out.Warn(err.Error())

}

// Send all messages in the order they arrive on the channel

for msg := range r.messages {

// If we're not online try to re-establish the connection

if !r.online {

if err = r.connect(); err != nil {

out.Warn(

"dropped %s message to %s (%s): could not connect",

msg.Type, r.Name, r.Endpoint()

)

// close the connection and go to the next message

r.close()

continue

}

}

// Send the message on the remote stream

if err = r.stream.Send(msg); err != nil {

out.Warn(

"dropped %s message to %s (%s): could not send: %s",

msg.Type, r.Name, r.Endpoint(), err.Error()

)

// go offline if there was an error sending a message

r.close()

continue

}

// But now how do we receive the reply?

}

}

The question is, how do we receive the reply from the remote?

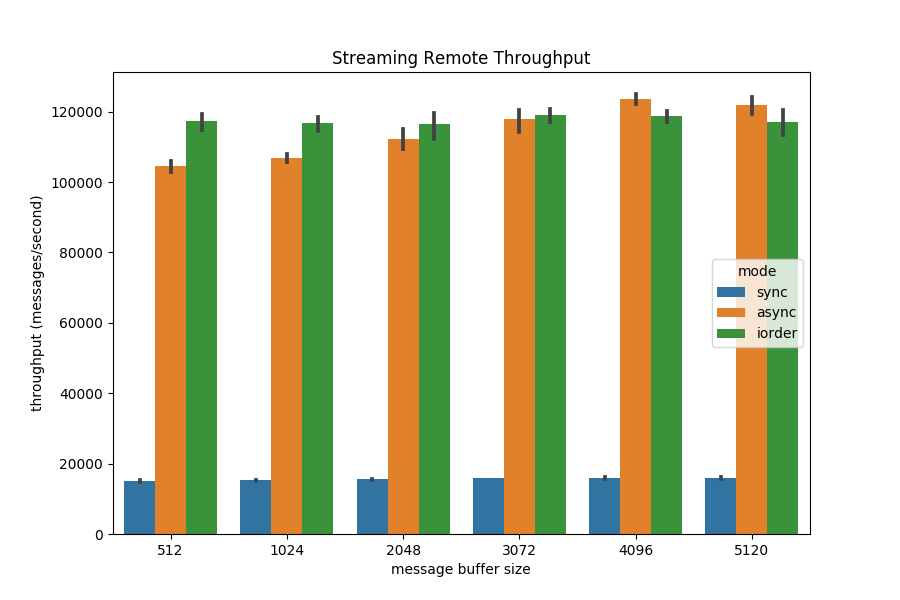

In sync mode, we can simply receive the reply before we send the next message. This has the benefit of ensuring that there is no further synchronization required on connect and close, however as shown in the graph below, it does not perform well at all.

In async mode, we can launch another go routine to handle all the incoming requests and dispatch them:

func (r *Remote) listener() {

for {

if r.online {

var (

err error

rep *pb.PeerReply

)

if rep, err = r.stream.Recv(); err != nil {

out.Warn(

"no response from %s (%s): %s",

r.Name, r.Endpoint(), err

)

return

}

r.Dispatcher.Dispatch(events.New(rep.EventType(), r, rep))

}

}

}

This does much better in terms of performance, however there is a race condition on the access to r.online before the access to r.stream which may be made nil by messenger routine closing.

To test this, I ran a benchmark, sending 5000 messages each in their own go routine and waiting until all responses were dispatched before computing the throughput. The iorder mode is to prove that even when in async if the messages are sent one at a time (e.g. not in a go routine) the order is preserved.

At first, I thought the size of the message buffer might be causing the bottleneck (hence the x-axis). The buffer prevents back-pressure from the message sender, and it does appear to have some influence on sync and async mode (but less of an impact in iorder mode). From these numbers, however, it’s clear that we need to run the listener in its own routine.

Notes:

- With sender and receiver go routines, the message order is preserved

- There is a race condition between sender and receiver

- Buffer size only has a small impact